This is the third post in this series where I explain why this statement holds true:

As a CAD Manager looking after AutoCAD users, or a power user looking after yourself, it’s worth your while to have a copy of BricsCAD handy.

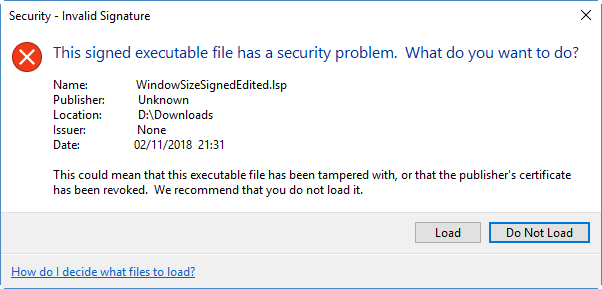

This post is about using BricsCAD as a mechanical and structural parts library for your AutoCAD users. As I mentioned in my last post in this series, I was writing a client-specific AutoCAD 3D training course recently. To demonstrate the concept of revolving profiles, and also to compare and contrast different styles of solid creation, I wanted to use a ball bearing as an example. The easiest way for me to get hold of an accurate example ball bearing model was to fire up BricsCAD (a few seconds) and select the part from the Standard Parts panel (a few more seconds).

It gets inserted as a block. After explosion to reduce it to 3D solids, I could then slice it in either BricsCAD or AutoCAD to form the basis for my example. I could save it at any stage in BricsCAD and open it in AutoCAD to continue to work on it seamlessly. What I can’t do is simply copy and paste from one application to another; you do need to save the DWG. You can then open it in AutoCAD or access the blocks using AutoCAD’s DesignCenter palette; if you’re doing this a lot you might want to point DesignCenter to a scratch DWG you keep handy for this sort of parts exchange.

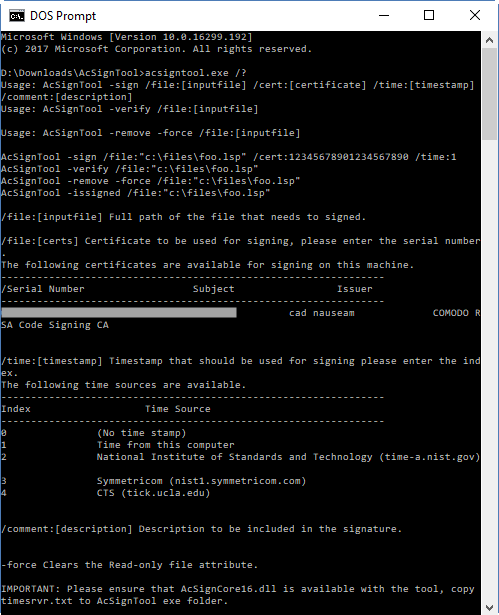

There are currently 13 sets of standards:

Although you may already have your own parts library, having access to a wider range of international standards may prove useful. Aussie steel sections? Go for your life, mate.

Just how much stuff is available? A lot. Each of the sets of standards has multiple sections, each section has many parts, and many of the parts have many sizes. Depending on the part, other parameters (such as bolt length) may also be available for a given size.

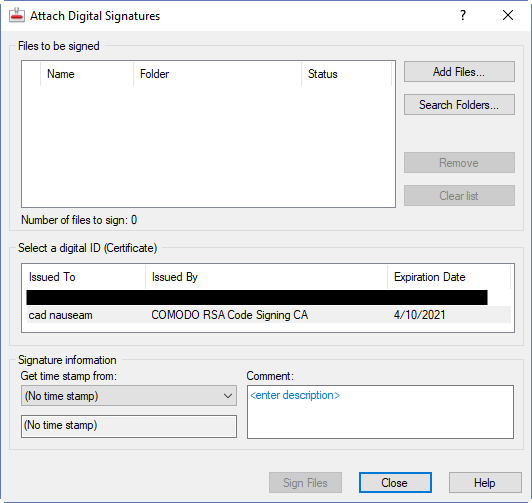

Here’s the full Standard Parts panel in action, in this case selecting a nut.

BricsCAD Pro and Platinum have 3D parametrics built in (and given the minor extra cost I’d suggest going for Platinum), so it’s quite feasible to use it as the basis for your own 3D parts library. If you’ve built up a few 2D dynamic blocks in AutoCAD, you’ll be quite capable of doing the same thing in 3D in BricsCAD. The methods are different but straightforward enough to teach yourself.

As pointed out in a comment by James Maeding, you can set up a network license or two and install BricsCAD on everybody’s PC, giving everybody access to the goodies without excessive cost. Bear in mind that like Autodesk, Bricsys charges a premium for a network license over a standalone one. Unlike rent-or-go-forth Autodesk, Bricsys allows you to have a perpetual license and the total cost of ownership is substantially lower.

By the way, this series isn’t theoretical, it’s all based on stuff I’ve tried out in the real world. For example, the network license software will happily coexist with Autodesk’s network license software on the same license server. The services ignore each other; no clash, no problem. My experience is that it works just fine on a virtual server.

It will cost you a few minutes to download and install of an evaluation BricsCAD and check out the included parts content for yourself.